Take 71: Is this the end of Access Journalism in Nepal?

Nepali media needs to do some serious soul-searching about how it missed the biggest story in Nepal’s modern history.

Welcome to Cold Takes by Boju Bajai, especially to all our new subscribers. Thank you for choosing to have us in your inbox 🙂

In this newsletter, we bring you a round-up of news and feminist views from Nepal and the Nepali internet. Also, we don’t clutter your inbox every week, cos we keep it cool and inconsistent here ;)

If you like what we do, you can support us by becoming our Patreon.

Last week when the Gen Z-led protests took over the streets of Kathmandu and across the country, it wasn’t just Nepal’s political class who were caught off-guard. Nepali newsrooms and journalists, who claim to know the “pulse of the nation” were also left scrambling to make sense of the crisis which unfolded rapidly.

When the power corridors that Nepali journalists once had access to, which shaped front page headlines, set agenda (and in the process also lifted the profiles of countless journalists with the right contacts) were burnt to the ground, Nepali journalists found themselves just as lost as the people who were looking to them for information and analysis. Discord, what’s that?

Hot takes are pouring in thick and fast about how last week was a reckoning for Nepali politics, and the men who’ve been in charge of the country for the last two decades. But it isn’t just politicians who need to deeply introspect. It is also a crucial moment for Nepali men running Nepali news organizations, which has largely remained free compared to its neighbours, and has continued to ask tough questions to those in power - to do some serious soul-searching, about how it missed the brewing discontent and anger among young Nepalis, both online and offline.

A majority of mainstream Nepali media from the national dailies to tv channels and even the newer online news outlets have always considered updates about power brokering, and which old neta met whom more newsworthy than stories of struggle and success of regular people. Despite the increasing reach and influence of social media, and the information ecosystem that’s been built on the internet, many mainstream Nepali newsrooms - old and new- rarely bother to report on it seriously.

No wonder, they missed the biggest story that turned our system upside down in two days and rewrote the rules of political movements in modern Nepal. And even in the aftermath of the protests, it was frustrating to see sections of the Nepali press trying to discredit the movement in different ways; take for example, Sudan Gurung, who has ended up becoming the face of the Gen-Z movement, and go after individuals who were at protest scenes, alleging they were behind all the destruction that took place, without bothering to get their side of the story.

Weren’t there other stories from last week that could have used the media's attention? For instance, why is the police so quick to fire live-rounds at people during protests? Not just on September 8, but in almost every protest in recent years. In 2023, two young men were killed during a protest by EPS aspirants in Lalitpur when the police used force. And less than six months ago, two people died and more than 45 people were injured in violent clashes between security personnel and pro-monarchy protesters in Kathmandu.

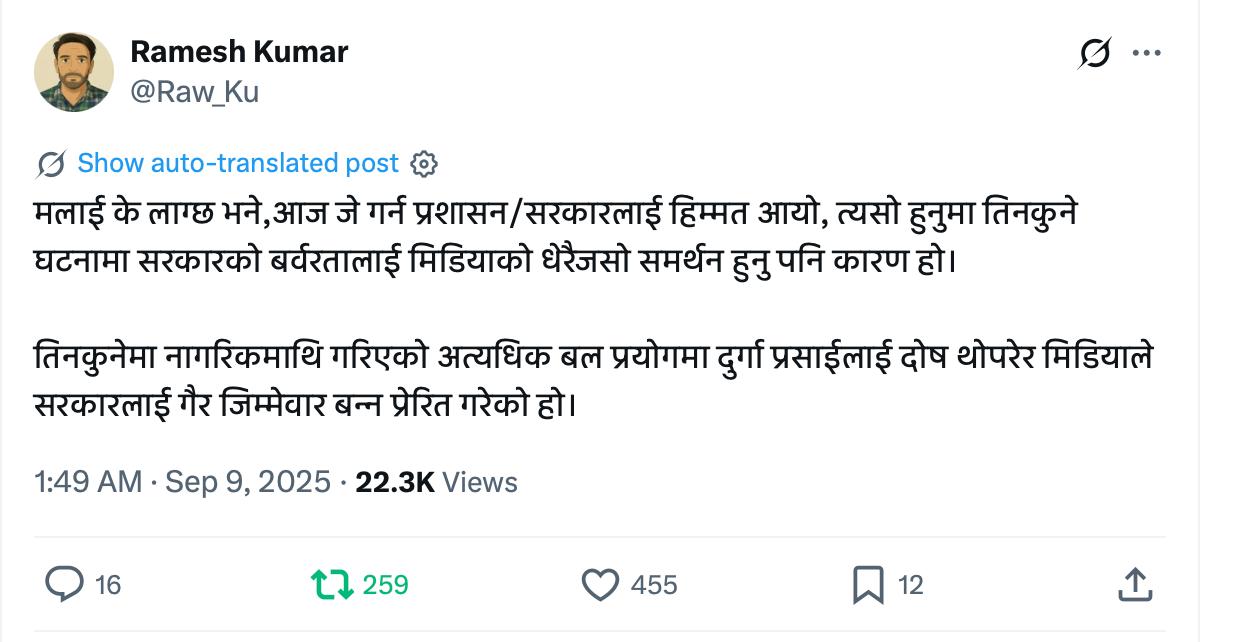

Except for a few social media posts here and there, Nepali media’s coverage about the use of force in such protests and its consequences, are rarely discussed. Last week journalist Ramesh Kumar suggested that the Nepali media’s failure to question the government’s brutality during the pro-monarchy rally in March could have “encouraged the government to act irresponsibly” during the Gen-Z protest.

Internet is reshaping politics, business, media, and culture, not just in Nepal, but all around the world. Unfortunately, Nepali media doesn’t sufficiently report about what’s happening in the different corners of the internet that young Nepalis inhabit. Until last week’s protest, Nepali media never thought of paying attention to the youth of Nepal and how their social media presence and their expression on social media was not something that was separate from their identities, their struggles, and their desires.

Didn’t it ever occur to all the वरिष्ठ पत्रकारहरु that these are things that shouldn’t have been dismissed?

The glaring absence of a dedicated beat reporting on the media industry itself also illustrates the opaque ways in which Nepali newsrooms have always operated. The ones responsible for asking questions are ironically the most squeamish when questioned about their own workplaces and work culture. The same people who are so quick to talk about freedom of expression and press freedom, when criticised, are hesitant to discuss the structural issues plaguing their own newsrooms.

For most of the gatekeepers at mainstream Nepali media, the disenchanted people spewing anger towards “jholey media and patrakars” on the comment sections are nothing more than trolls. But last week when violence broke out, resulting in the destruction of public and private properties, including media houses, it seemed the people’s anger at the larger system spilled over to everything and everyone who might appear to be part of the establishment.

Pranaya Rana, who writes Kalam Weekly newsletter, painted chilling scenes from Kathmandu where some people were trying to burn journalists in a van saying “Sab patrakar jholey ho.”

According to the Federation of Nepali Journalists, several journalists were injured during last week’s protests while they reporting from the frontlines, and many were hurt when their newsrooms were attacked. Some journalists in Kathmandu told us they were hesitant to go out and report, often hiding their press cards when they are in the field. Despite this they persevered and continued reporting all week.

Journalist Prateebha Tuladhar’s recent piece in Nepali Times illustrates the growing distance between Nepali media organizations and the general public.

She writes, “During the April 2006 street protests, hundreds of people had stopped outside the Kantipur complex in Tinkune to clap and show gratitude for the good journalism it had done. I worked there at the time and I remember looking out the window, tears of gratitude streaming down my face.

The same establishment received a different kind of treatment this time.”

When the rebuilding starts, it is important that Nepali newsrooms find ways to counter the intense antagonism towards mainstream media. Researchers have been screaming from the rooftops about people’s low trust in the media, and what newsrooms can do about it. But Nepali media has rarely tried to make an effort to understand why their credibility is eroding and how it can win back people’s trust, especially among younger people, who didn’t grow up reading and believing everything the media reported.

Young Nepalis have made it possible for us to believe that there can be an alternative to our political system, which we all knew was corrupt, rotten, but we had come to accept as the norm. It is about time Nepali mainstream media also view this moment as a rejection of their old ways of doing journalism that was largely about access to old, corrupt corridors of power centers, and work towards building newsrooms that reflect the communities they serve.

Bhrikuti Rai

Two years ago when we interviewed journalist Binu Subedi, she worried that Nepali media was undergoing a precarious transitional period, since the second Jana Andolan days, when being a journalist was a badge of honor, and a handful of news organizations were gatekeepers of information and wielded power to shape public discourse.

She speaks candidly about the failure of Nepali news media to report extensively on issues concerning the people and communities from the margins of Nepali society with the same enthusiasm and perseverance that goes into reporting about the power plays of powerful men.

“Newsrooms are a reflection of our society… and we need to introspect, and repeatedly ask ourselves whether or not what we (as journalists) are doing is right or wrong, only then we can break free from the prejudices and move in the right direction,” she says.

In this hour-long conversation, Subedi talks about the challenges faced by media outlets today where corporate and political interests are a constant threat to fair and free journalism. She also comments on the problematic hierarchies and power relations entrenched in patriarchal institutions like mainstream media houses.

Here are some highlights from our conversation:

To listen to the full episode click below:

Related readings:

Access Journalism Is a Fool’s Errand, Dame Magazine

The Media and its malcontents, Kalam Weekly

“Under Narendra Modi, access has become conditional on the journalist’s ideology”, Reuters Institute

Why are police so quick to shoot during protests in the Tarai?, The Record